This is the UK edition. For the US we turned to Ivan Kramskoi’s Portrait of an Unknown Woman (1883). Aren’t they great?

‘I was told you were in the Crimea.’

Yashim blinked. ‘I found a ship. There was nothing to detain me.’

The seraskier cocked an eyebrow. ‘You failed there, then?’

Yashim leaned forwards. ‘We failed there many years ago, efendi. There is little that can be done.’ He held the seraskier’s gaze. ‘That little, I did. I worked fast. Then I came back.’

There was nothing else to be said. The Tartar khans of the the Crimea no longer ruled the southern steppe, like little brothers to the Ottoman state. Yashim had been shaken to see Russian Cossacks riding through Crimean villages, bearing guns. Disarmed, defeated, the Tartars drank, sitting about the doors of their huts and staring listlessly at the Cossacks while their women worked in the fields. The khan himself had fretted in exile, tormented by a dream of lost gold. He had sent others to recover it, before he heard about Yashim – Yashim the guardian, the lala. In spite of Yashim’s efforts, the gold remained a dream. Perhaps there was none.

At the beginning of The Janissary Tree, Yashim has just returned to Istanbul, telling himself that ‘anything was better than seeing out the winter in that shattered palace in the Crimea, surrounded by the ghosts of fearless riders, eaten away by the cold and gloom. He had needed to come home.’

One irony that won’t be lost on anyone following recent developments in the Crimea is that Catherine the Great stole the territory illegally in the first place. By the treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, signed between the Ottomans and the Russians in 1774, Crimea was to remain in Ottoman hands. Nine years later, the Russians seized it.

When I wrote lately about putting some of my backlist on Kindle, I wondered aloud if this was a Good Thing – or the Slippery Slope.

The truth is, I suppose, Kindle is here and here to stay.

I recommend this article by George Packer in the New Yorker, about Amazon and their total control of information.

Be that as it may, for authors I think it is the new best thing – and here is one reason for thinking so.

After my GREENBACK: The Almighty Dollar and the Invention of America inspired a 5 part BBC Radio 4 series at the end of last year, I revised and republished the book as a Kindle download. Here it is:

It was immense fun – not least because every author, coming at a book after a gap of several years, sees what he wants to do differently this time round. That’s why would-be authors are often advised to put their manuscript in a drawer and forget about it for a while: when they come back to it they have the advantage of reading it anew, as a reader, not as the writer. That clunky paragraph? That darling line which you should have murdered first time round (cf. murder your darlings: Auden)? That digression which seemed so fascinating when it was something you had just discovered yourself?

Well, you follow my line of thought here, no doubt.

With a published book there’s usually nothing to be done about it – the book is there, it’s done, pasted between boards and out in the world.

But with GREENBACK for Kindle, I got a second bite at the cherry.

I trimmed it. I boosted up the argument I had made too faintly. I corrected the error a kindly reviewer had mentioned, en passant. I lopped a whole six pages – that digression! – from a chapter on the American Civil War. I performed literary liposuction on every chapter and the book was better for it. Honest. I made it zippier, funnier and more focussed.

And then, in about twenty minutes, I published it on Amazon.com. On Amazon.co.uk. On Amazon.fr and Amazon.de…and so on.

The story of the world’s favourite currency available to the whole world.

And here’s another reason for liking this process, one that should resonate with readers and authors but not, maybe, with publishers.

It’s control. I set the look, and the price – and when I want to get more people to see the book, maybe buy it – I can do a price promotion.

Right now, GREENBACK is available on Amazon.com at a ‘special’ price – ie, cheap. And that has the astonishing and slightly alarming effect of raising sales tenfold.

I cut the list price – $7.99 – by half. And have just sold ten times as many copies of the book. Go figure.

At $3.99 it is, I think, too cheap. It’s less than a throw-away magazine, or a skinny latte, or a bowl of olives in a restaurant. And it took me four years’ work.

On the other hand, writers want readers.

Ps But hurry! The Offer, as they say, Ends Soon!

Looking through an album of old photographs the other day we came across this entertaining Victorian group.

Effie, on the right, has either just lost at racquets or merely resents her sister Mary’s engagement to Captain Pilkington (together, back left). Mrs Bulteel, the photographer’s mother, isn’t too sure of Captain Pilkington herself; either that, or she flatters herself she looks best in profile. At the centre of the group sits Bessie, powerful and relaxed, wearing a floppy hat.

Look more closely. Unfazed by the towering emotions playing out around her, Bessie seems to be chatting to someone on her mobile phone.

Nothing breaks the mood like a duff note – a glaring anachronism, a remark made in inappropriate slang, or the moment when a character’s eyes change mysteriously from blue to brown. On the other hand, it’s important not to get too bogged down in verifying details when you’re writing. After all, it’s the story that counts, isn’t it?

Copy editing – which we’re doing now with The Baklava Club, Yashim’s fifth Istanbul adventure – is the time to address those niggles. Is the name of the street spelled correctly? Do baby artichokes really come into market before the asparagus? And the guns – are they alright?

A fowling piece by the celebrated French gun-maker, Nicholas-Noël Boutet (1761-1833). It was allegedly plundered from the baggage train of Joseph Buonaparte, King of Spain, following Wellington’s victory and rout of the French during the Peninsular War at Vittoria on 21 June 1813.

The guns in question are a pair of fowling pieces belonging to Count Palewski, Polish ambassador in Istanbul, and Yashim’s friend. They were made in the early years of the nineteenth century by the Parisian gunsmith Boutet: exceptionally light and very beautiful. For this, and related detail, I consulted the Royal Armouries Museum, and my thanks are due to Mark Murray-Flutter who not only provided me with gunnery jargon but ultimately re-wrote a few sentences of The Baklava Club himself.

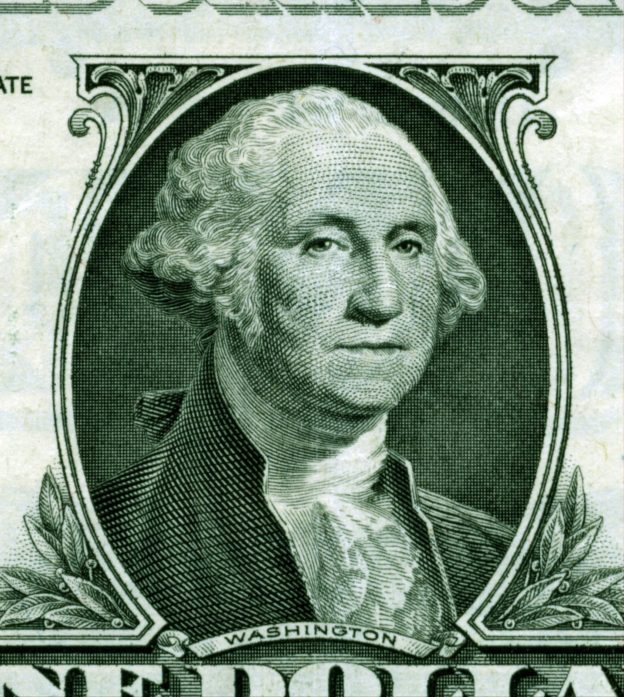

Gideon Fairman was a blacksmith who developed an aptitude for engraving, and eventually chose to work on a reproduction of probably the best-known portrait in world history, Gilbert Stuart’s 1795 portrait of President Washington.

Fairman’s rendering of Stuart’s Washington has been reproduced at least 14 billion times since it first appeared on the US dollar bill in 1929. It finds its way onto T-shirts, chocolates and government web-sites. By all accounts it is taken from one of the worst likenesses of Washington ever produced: infinitely more human portraits of the President were done by the Philadelphia artist Rembrandt Peale. It was not really Gilbert Stuart’s fault that his picture worked out so pumpkin-like and expressionless. Stuart was first-rate: he had worked in London with the great progenitor of American painting, Benjamin West, and competed for sitters successfully against some of the giant names of British art.

Unfortunately for Stuart, Washington sat for him while he was trying to get used go a new set of false teeth, ‘clumsily formed of Sea-horse Ivory, to imitate both teeth and gums, [which] filled his mouth very uncomfortably…’ The president clapped them in every time he sat, hoping that they would grow more comfortable if he used them; in the end he abandoned them. ‘Mr Stuart himself told me that he never had painted a Man so difficult to engage in conversation, as was his custom, in order to elicit the natural expression, which can only be selected and caught in varied discourse. The teeth were at fault,’ explained Rembrandt Peale.

He might have enjoyed his innocent schadenfreude rather less had he known how the American public would always like this stiff, stubborn portrait, mutton-jaw and all. Stuart produced a total of three portraits of Washington and then, seeing how his bread was buttered, 111 replicas. In fact he lived off Washington’s face. Long before his portraits of the President appeared on the currency he lightly referred to them as his ‘one-hundred dollar bills.’

The original, so-called Athenaeum head was never finished; like its companion piece, a portrait of Martha Washington, it remains a sketch on oils and may be seen at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

An extract from my biography of the dollar, GREENBACK: The Almighty Dollar and the Invention of America.

The BBC recently made a radio series on the history of the American dollar, and asked me along to talk about it, as the author of GREENBACK: The Almighty Dollar and the Invention of America.

Surprised? Well, it’s not a Yashim mystery, for sure: it’s the book I turned to after I’d written the story of the Ottoman Empire, Lords of the Horizons. I wanted to describe the rise of another empire – and zooming in on the story of America’s money seemed the way to do it. Oblique, maybe – but an astonishing tale. BBC Magazine ran this piece on the series.

As the shows aired, I took a look at GREENBACK again. I had to agree with a reader who recently noted striking parallels between the nineteenth century financial skulduggery it describes, and the 2007 financial crisis. It was a pity, he thought, that I hadn’t published the book after Lehman Brothers collapsed, the world banking system teetered, and the euro – that other new currency – began to unravel, a nightmare for countries in the grip of a deep and problematic recession.

Coming at GREENBACK after a lapse of years, I read with a fresh and readerly eye – a version of the old put-it-in-a-drawer-and-leave-it-for-six-months advice handed out to aspiring writers. I saw where the book lagged, and where it needed a tweak or a correction. So over Christmas, between the holly and the pudding, I revised GREENBACK wholesale, and wrote a new preface. I even tracked down a half-chapter which for some unaccountable reason had fallen out of the original manuscript, and restored it – it’s about Sir Walter Ralegh’s search for American gold, and the fate of the first settlement at Roanoke, in Virginia. It makes for spooky reading, and sits well with the whole thesis about the role of money in America.

I’ve now published the revised book on Kindle. Here’s a selection of the reviews:

“The story of the dollar is the story of the country’s independence and emergence – and it couldn’t have been told more engagingly.” The Guardian.

“His engaging ‘Greenback’ … approaches the empire of the dollar with a foreigner’s sense of wonder and a dry wit.” The New York Times.

“Splendidly entertaining, fast-paced, and revelatory. . . Goodwin, who possesses the gift of concision and an impious eye for character, is a master at weaving together monetary theory and historical anecdote.” The Boston Globe

“A fanciful and charming meditation on money and the role it plays in our society, history, and culture. . .[Written] with flair, anecdote, and amusing aside.. . . A beguiling narrative.” Chicago Tribune

“[With] tidbits and tales that read more like novels. . . Greenback is a giddy ride into the past.” Barron’s

“A riveting story with a quirky cast of American characters that includes a few of the Founding Fathers, inventors, counterfeiters, secret agents, bankers, and swindlers.” The Christian Science Monitor

I’d like to wish you a very happy Christmas, by sharing with you the Christmas Story which Richard Adams and I have sent out to all our friends this year. It was written by the late John Michell, and has only the most tangential relevance to Yashim, or Istanbul – see the forthcoming novel THE BAKLAVA CLUB for more details…!

Birds & Flowers of Eastern Siberia copy

MERRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR!

Apologies to anyone who downloaded On Foot to the Golden Horn: A Walk toIstanbul to their Kindle and discovered that it was

squashed up

against the left hand margin

rendering it all

but unreadable!

It has been fixed, and I believe the Kindle will update your copy automatically. Maybe you have to push a button, but that’s it.

If you don’t know, it is an account of a trek I made from Gdansk to Istanbul in the Spring of 1990, walking for almost six months through the villages and landscapes of eastern Europe – Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and finally Turkey. It was the journey that kindled my fascination with the Ottoman Empire, as we walked through a world touched by its lingering influence – a minaret, say, in northern Hungary, or an encounter with a fierce shepherd dog, or a gulp of very strong black coffee, or the sight of gypsy women in glorious swirls of coloured skirts… Istanbul, or Constantinople, was in the music, and in the orthodox churches, and in the air.

My companions were Mark and my girlfriend, Kate. Mark, understandably, decided to head off on his own, on another route, about half way through the trek; but Kate and I walked into Istanbul together. The book ends there; but the story continues…

When I visited Albania, in 1996, the imam at the Tirana mosque very kindly invited me to accompany him up the minaret. I shuffled my feet nervously onto the balcony while he issued the call to prayer, gazing down over the roofs of the city, and away to the encircling mountains. Far off, high on the mountain flank, I could just see Krujë, from where Scanderbeg defied the Ottoman forces in the 15th century for almost thirty years.

Albania is a mountainous country of about 4 million people, which was all but closed to the outside world from 1945 to the early 1990s, when its secretive communist regime finally collapsed. It’s a land of ancient ruins, glorious terraced hills, unspoilt Mediterranean beaches, and really hairy driving conditions. Here’s a gypsy playing his bagpipe – a reminder that Byron thought the Albanians were close to the Scots, with their kilts and their clans. He, of course, had himself painted in Albanian dress (above).

And here’s the wonderful trailer the Albanian publisher produced – 52 seconds of true Albanian atmosphere!

Once conquered, the Albanians did a reverse take-over of the Ottoman Empire. Their horizons, bounded by the mountains and the seashore of their own small country, expanded. Albanian devsirme boys went on to dominate the Janissary Corps. The Köprülü provided a dynasty of Grand Viziers. Mehmed Ali ultimately seized control of Egypt, founding a royal line that fell from power in 1956. So when I spotted Ataturk’s double in the street outside my hotel, everyone shrugged: Mustafa Kemal was Albanian, they assured me.

Now a site has been cleared for a new mosque nearby, but the delightful roccoco building erected in 1703 is in immaculate condition, decorated inside and out with floral panels and these delightful glimpses of an Ottoman paradise.