Since the US and UK banned laptops and tablets from the airplane cabins on flights originating in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, Tunisia and Saudi Arabia, I’ve read some really daft articles addressing the desperate question: what can I do on the plane?

Here’s one, from Bloomberg: Hacks to Survive a Twenty Hour Flight – without a laptop or tablet!

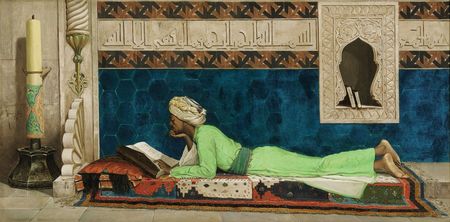

One answer might be: read a book. Revolutionary? Perhaps all first class travel could look like this?

Here’s my list for travellers coming out of Turkey:

Three Daughters of Eve by Elif Shafak

The latest novel by the wonderful Elif Shafak, who first burst onto the scene with her punchy, funny and tragic novel, The Bastard of Istanbul. Elif writes about women negotiating their power and their position in a man’s world, and she does it with sly humour, tenderness, and a wonderful feel for historical time and place. The action kicks off when a beggar snatches the handbag of a wealthy Turkish housewife on her way to a smart Istanbul dinner party. Out drops an old photo… and with it, a life and love that Peri has tried to forget.

Istanbul: Poetry of Place, edited by Ates Orga

Packed with poetry and a little prose, all set in the former capital of the Byzantine and the Ottoman empires, Istanbul: Poetry of Place brings you the voices of the city’s inhabitants, from sultans to modern-day feminists.

Snow by Orhan Pamuk

Complex, fragmentary, unreliable and poetic, this thoroughly postmodern novel abounds with puns, ironies, double-takes and imponderable conflicts of love, faith and social justice, reflecting not only aspects of the human condition but also of 20th-century Turkey’s preoccupations with secularism, religious freedom and revolution. In the city of Kars, a young journalist, Ka, comes to investigate a spate of suicides relating to the wearing of headscarves – and opens up a kaleidoscopic world of claims, counter-claims and conflicting priorities.

Turkey: a Short History by Norman Stone

A fanfare for modern Turkey and a vivid, provocative, often funny, always insightful account of how it came about. Stone pulls together his accomplishments as a philoturk, a philologist, controversialist and narrative historian to sweep his readers along a short crash course in Turkish origins, their history and current challenges. If you don’t really know why a portrait of Ataturk hangs in almost every shop in Turkey, read this book.

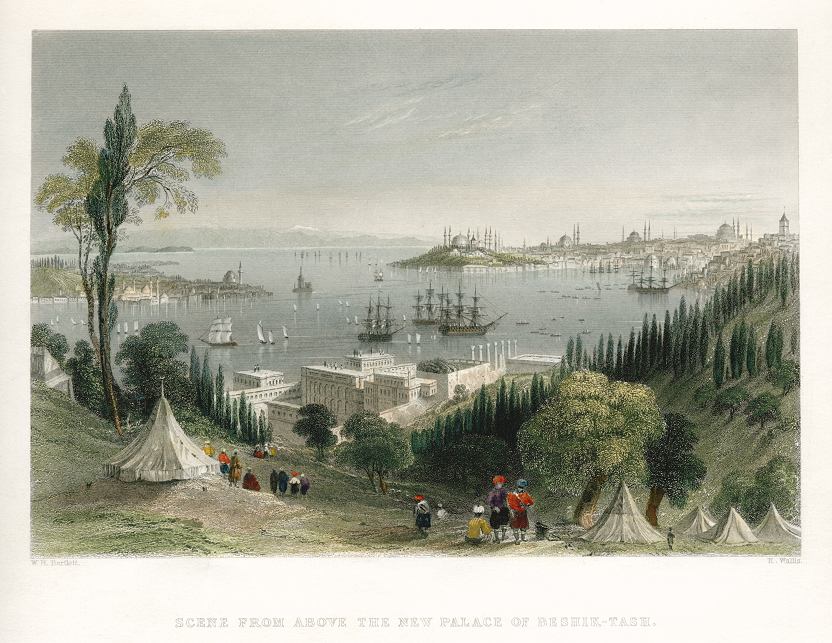

Constantinople: City of the World’s Desire by Philip Mansel

The definitive history of the city from 1453, by one of our finest historians, also explains how a multi-ethnic, polyglot empire was controlled by a single dynasty for more than 600 years. Mansel mines a vast range of sources to bring the fashions, pomp and politics of this ancient world capital to life.

Birds without Wings by Louis de Bernières

I keep picking this up – and putting it down again, because I can’t quite face the onrushing tragedy. Needless to say, it’s the story of a doomed love affair between Philotei and Ibrahim, as relations between Greece and Turkey collapse in the First World War; prelude to the massive population exchange of 1923, which ended Greek settlement of Asia Minor. Gallipoli is in it; so is Ataturk; so are some characters from Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. De Bernières insists this is the better book and I believe him.

Eothen by AW Kinglake

The title, which means “from the east” is, as the author points out, the hardest thing in the book, a sly travel account purporting to be written by a Victorian hooray which makes for spectacularly funny reading. Jonathan Raban has described the narrator as having the “sensibility of someone who is a close blood-relative of Flashman”: witness his thoroughly waspish account of a meeting with Lady Hester Stanhope. Typical, too, is his insouciance towards the plague in Cairo, which claims his heroic doctor while the narrator survives unmoved.

A Short History of Byzantium by John Julius Norwich

The three volumes of his magisterial history, boiled down into one, may seem too condensed at times, but Norwich deftly and entertainingly outlines the often outrageous story of an empire that lasted 1,123 years and 18 days. It is as good on Byzantine art and church matters as on the peccadilloes of the emperors – and their triumphs.

Rebel Land by Christopher de Bellaigue

Caught up in a journalistic furore after his mention of the Armenian massacres that occurred in the dying days of the Ottoman empire, de Bellaigue decided to find out for himself what may have happened. He settled on – and in – the town of Varto, which once had a huge Armenian population. Without delivering any final answers, de Bellaigue’s beautifully written account of his experiences with locals, secret policemen and even exiles still sheds light on this intractable issue, if only to illuminate the complexity of the situation both then and now.

The Sultan’s Seal by Jenny White

The first of the Kamil Pasha detective stories, set in the dying days of the Ottoman Empire, kicks off with a body on the beach. Kamil Pasha, the Anglophile Ottoman detective, must draw together the threads of this murder and of an older, unsolved crime, sifting through the murky waters of late Ottoman politics and society. Sequels are The Abyssinian Proof and The Winter Thief.

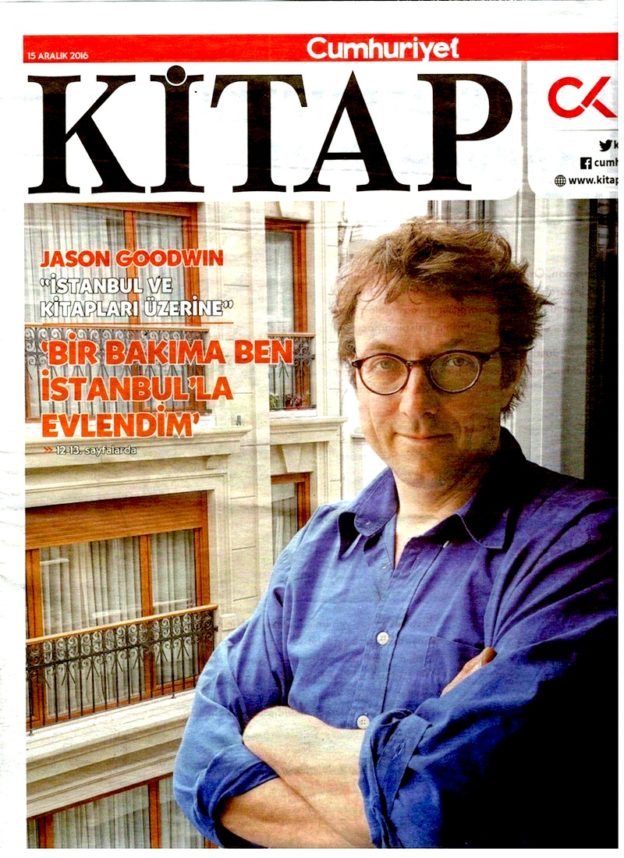

Yashim: Don’t forget that all five Yashim novels are available as a set from Amazon.com and from Amazon.co.uk – and in dozens of languages, too. Meanwhile The Janissary Tree and The Snake Stone are published in Turkey by Pegasus as Yeniceri Agaci and Yılanlı Sütun